The Barracks, New Norfolk, 12/2/2022 to 27/2/2022

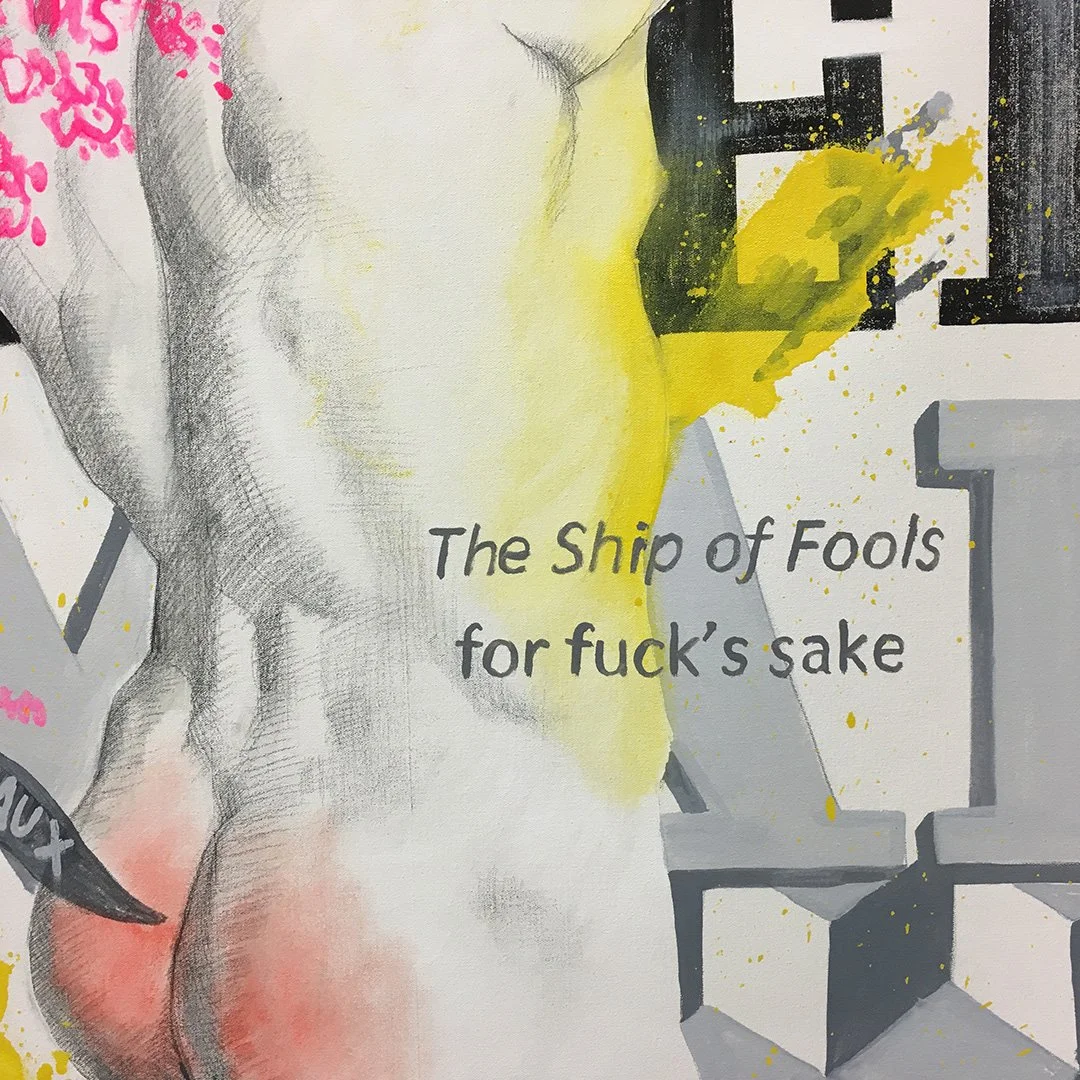

In When the Smoke Clears, Neil Haddon presents a new body of paintings that are influenced by his research into the life of James Kelly (1791 – 1851). Kelly was master mariner, whaler, and harbour master.

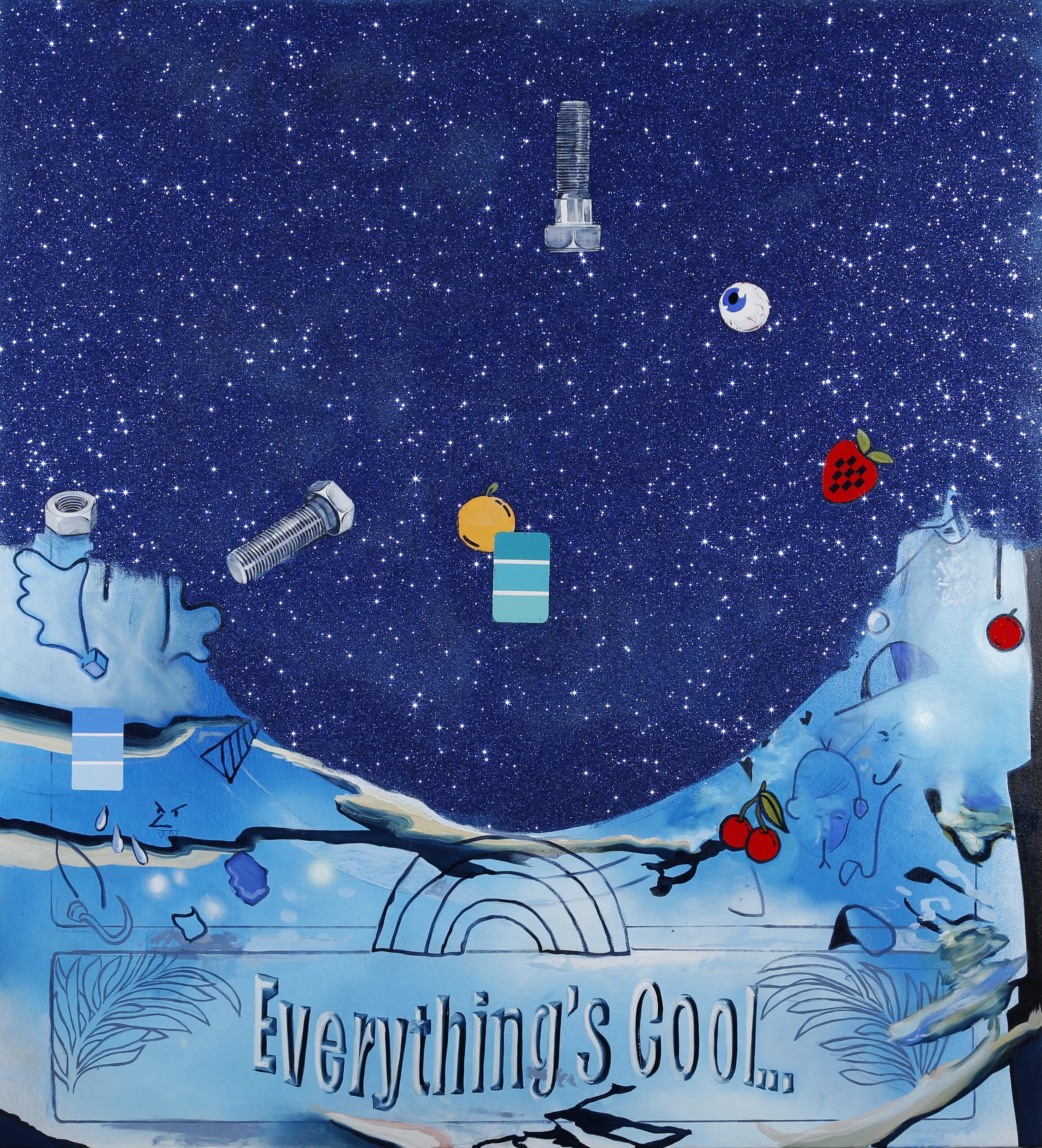

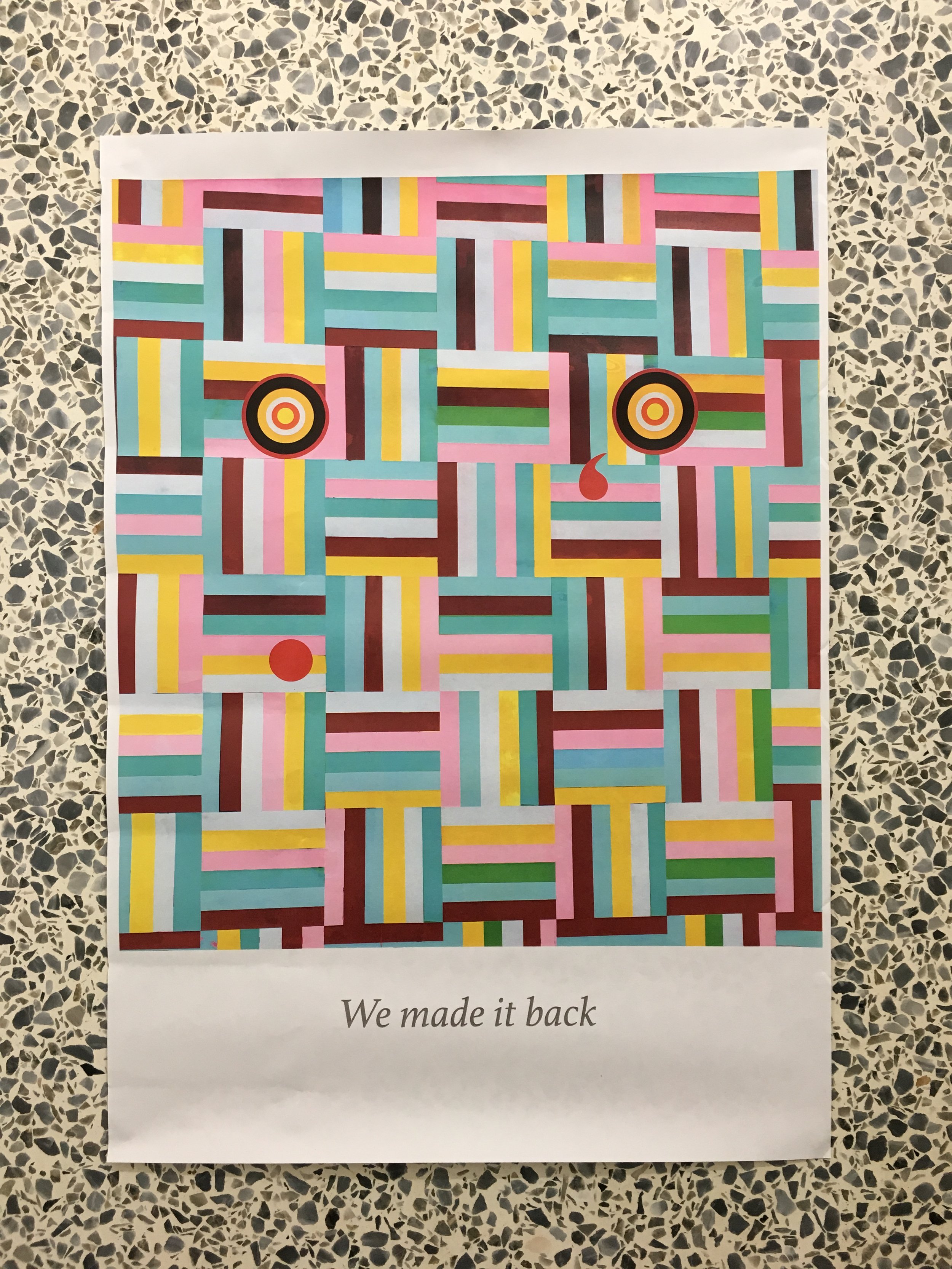

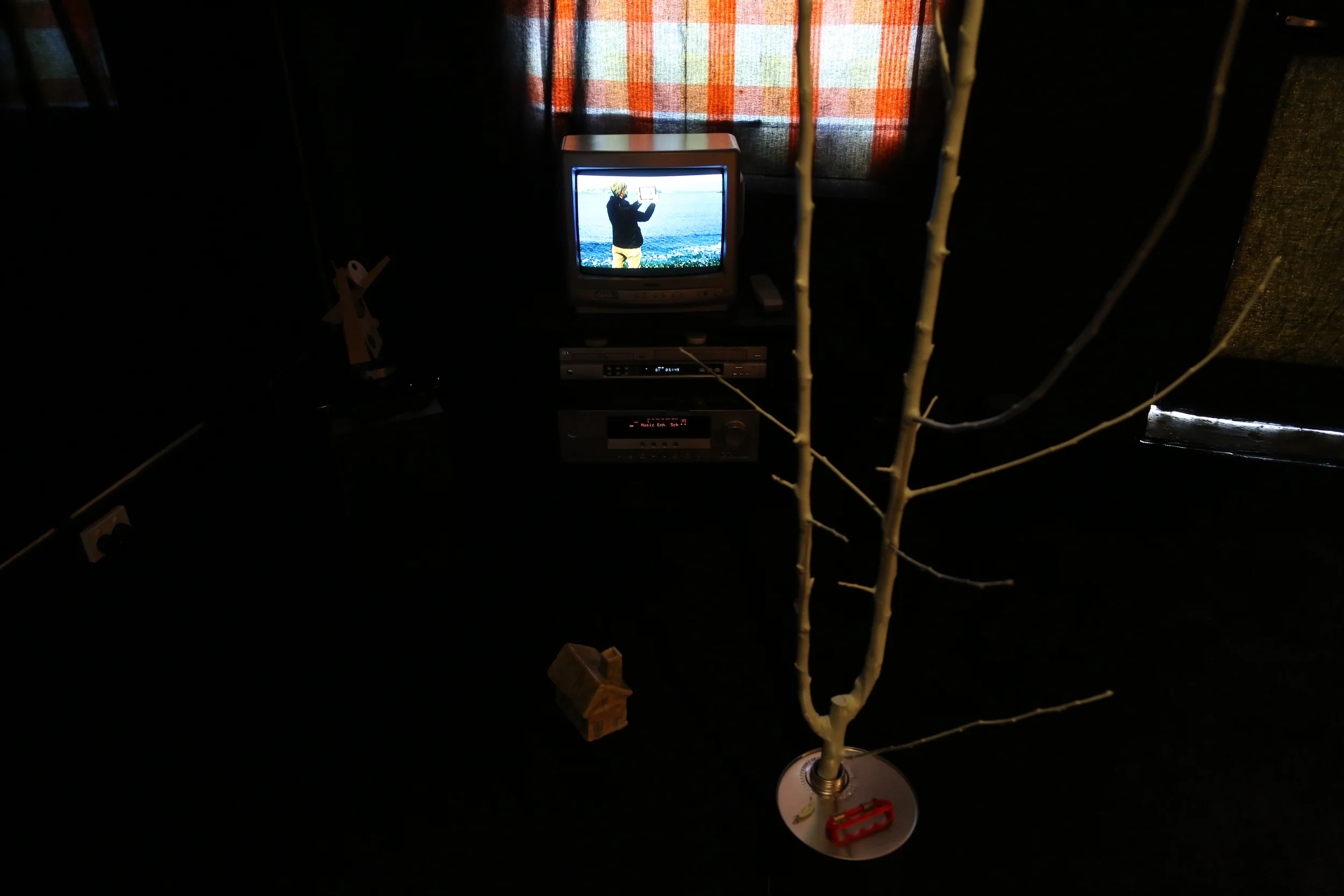

Although Haddon arrived in Australia more than twenty years ago, his experience of migration echoes that of Paul Carter, who writes, 'the migrant does not arrive once and for all but continues to arrive, each new situation demanding a new set of responses’. (1) When the term ‘migration’ is brought together with artistic production, it conjures up a distinctive way of working whose very nature is transitory, moving and unfixed. The project is situated within the field of ‘migratory aesthetics’, a form of artistic practice whose chief characteristics are spatial displacement and multi-temporality. The paintings in When the Smoke Clears employ the tools of migratory aesthetics, including the use of dislocated, fragmentary imagery, a compounded sense of past and present time, and memory, associations and representations formed elsewhere. The aim is to provide new purchase on stories and histories relating to Kelly, treating the historical record as a poorly understood territory yet to be discovered and named.

Some notes on When the Smoke Clears

Last year I read James Kelly's handwritten account of his 1815 circumnavigation of Tasmania, First Discovery of Port Davey and Macquarie Harbour. (2) This account was written at least six years after the events, probably longer. As Kelly and his crew rowed through the narrow entrance to a vast natural harbour on the West Coast of Van Diemen’s Land, they passed through clouds of smoke generated, Kelly speculates, by Tasmanian Aboriginal hunters. Kelly named the place ‘Macquarie Harbour’.

I also read The Remarkable Captain James Kelly of Van Diemen's Land by amateur historian Anthony Hope.

And a letter from James Bruni, Kelly's son, written while he and his younger brother were at boarding school in England. In the letter, the son asks his father to send him ‘a couple of knives and some marbles.’ (3) James Bruni was killed by a ‘blow from a whale’ when he was 21. (4) His brother, Tom, died in a boating accident on the River Derwent one year later when he was 16.

As the past pulls away and the future begins

I say goodbye to all that as the future rolls in

Like a wave

And the past with its savage undertow lets go (5)

I am a migrant to Tasmania. I wanted to enter the story of Kelly and his family as if I were discovering it for the first time, bringing to bear associations, empathies and memories formed elsewhere. Aspects of Kelly’s story have been woven together with mine, images from my background set in dialogue with his; at times critical, at times empathetic, often ambiguous and unclear, as if shrouded in smoke.

In The Pensive Image, Hanneke Grootenboer proposes that some paintings ‘confront us in such a way that our wondering about the work of art – its subject of meaning – is transformed into our thinking according to it’. (6) A migratory way of thinking and working, the new response, becomes a tool for critical engagement.

This exhibition takes place on lutruwita (Tasmania) Aboriginal land, sea and waterways. I acknowledge, with deep respect the traditional owners of this land, the palawa people. I pay my respects to elders past and present and to the many Aboriginal people that did not make elder status and to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community that continue to care for Country. I recognise a history of truth which acknowledges the impacts of invasion and colonisation upon Aboriginal people resulting in the forcible removal from their lands. I acknowledge that visual culture and art played a part in that colonisation and stand for a future that respects and acknowledges Aboriginal perspectives, culture, language and history.

A selection of paintings in this exhibition will be shown at the Tongji University Museum, Shanghai, China in November 2022 alongside the work of Chen Ping and Anthony Hope. I am grateful to Chen Ping for initiating this project.

This project was assisted through Arts Tasmania, supported by the Tasmanian Government, and the University of Tasmania, School of Creative Arts and Media.

Neil Haddon, January 2022

Carter, P. 1992, Living in a New Country: History, Travelling, Language, Faber and Faber, London, p.6

Collection of the Royal Society of Tasmania, RS99/1

James Bruni Kelly, letter to his father, Collection of the Royal Society of Tasmania, RS7/91a

Inscription on the Kelly grave, St. David’s Park, Hobart

Nick Cave, Sun Forest, 2019

Grootenboer, H. The Pensive Image, 2020, p.6

For enquiries about the purchase of work in this exhibition please contact: info@bettgallery.com.au or nhaddon@netspace.net.au

Migratory Aesthetics, Pastiche and Painting: an exploration of migratory experience by Neil Haddon available here: https://eprints.utas.edu.au/37806